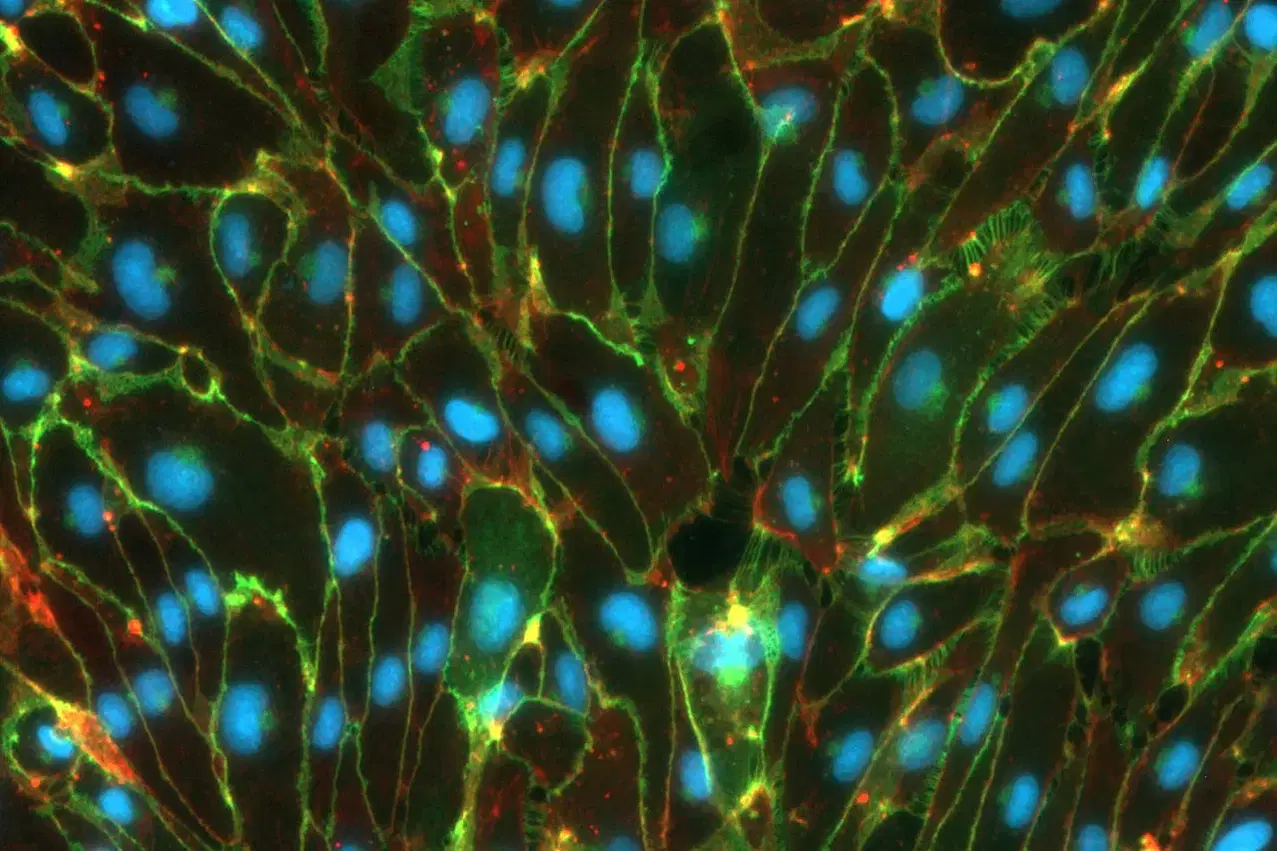

Human model of blood-brain barrier

The brain is a unique organ within our body and thus all the more worthy of protection. And so the blood-brain barrier (BBB) prevents potentially harmful substances from entering the brain from the bloodstream. Disruptions of this protective wall are involved in the development of major brain diseases such as strokes and Alzheimer’s.

Now, researchers from LMU University Hospital, led by Professor Dominik Paquet and Professor Martin Dichgans from the Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (ISD), have succeeded in constructing a functional human blood-brain barrier from human stem cells in the laboratory, allowing them to investigate pathological processes in detail. The findings of the scientists, together with lead authors Dr. Judit González Gallego and Dr. Katalin Todorov-Völgyi, have been published in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

Over the past decades, hundreds of drug candidates designed to tackle conditions like Alzheimer’s disease have appeared so promising in animal experiments that they were subsequently tested on humans in elaborate studies — for instance, in the search for new treatments against Alzheimer’s disease. Yet, only one of these was ultimately approved to treat patients.

This poor success rate illustrates how urgently drug development needs experimental models that are based on human cells and can better reflect the effects and risks of potential new drugs. In addition, basic research relies on realistic models to decipher the genetic and molecular foundations of brain diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and stroke.

One of the open questions, for example, is what role disorders of the blood-brain barrier play in neurological diseases. The BBB is a complex system of multiple cell types – primarily endothelial cells forming the innermost layer of blood vessel walls, as well as smooth muscle and glial cells.

These cells form an almost impenetrable passive barrier, while also actively ensuring that substances that are important for the brain are let through and potentially dangerous substances from the blood are kept out. “In this way, the barrier creates a special environment in the brain, without which neurons could not function properly,” explains LMU neuroscientist Paquet.

In 2018, his team began to reconstruct a model of the blood-brain barrier in the laboratory, based on induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from humans. From these, the scientists at the Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (ISD) generated all the necessary cell types that make up the blood-brain barrier. With a few tricks from molecular and cell biology, the researchers got these cells to form functioning three-dimensional tissue in a gel-like matrix, which in microscopic images closely resembles blood vessels in the brain.

“In close collaboration with the laboratory of Martin Dichgans, we also managed to demonstrate that this model can be used to study disease processes,” continues Paquet. “For example, we discovered that the blood-brain barrier no longer functions correctly when a certain risk gene that occurs frequently in stroke patients is modified in the endothelial cells,” explains Dichgans.

The experimental system is now available to scientists worldwide who want to illuminate research questions relating to the blood-brain barrier. “It can be quickly established in any laboratory in just a few weeks,” says Paquet, who hopes the innovative model will accelerate the development of novel therapies for neurological diseases.